Protection of Three Dimensional Trademarks in Japan

地域:日本

業務分野:商標

カテゴリー:その他

『Yuasa and Hara Intellectual Property News』Vol.22,

ユアサハラ法律特許事務所、2007年8月

柳生 征男

IPHC decisions :

Protection of Three-Dimensional Trademarks in Japan

The Intellectual Property High Court (IPHC) has recently rendered two historically memorable decisions. On November 29, 2006, the IPHC held invalid Reg. No. 4704439, a three-dimensional chick-shaped trademark for cakes. This is the first Japanese case in which a registered three-dimensional trademark has been cancelled. On June 27,2007, the IPHC reversed the decision rendered by the Trademark Trial and Appeals Board (TTAB) of the Japan Patent Office (JPO) refusing a registration of a three-dimensional trademark for a small, pen-shaped flashlight that had been sold over a long period in Japan by a US corporation, Mag Instrument, Inc. Although the JPO could have appealed to the Supreme Court against the decision, they unofficially indicated that they would respect the IPHC’s decision. Thus, the case will be returned to the TTAB for re-examination. The TTAB is bound by the decision rendered by the IPHC, and will issue a decision allowing a registration. Thus, it can be said that the decision is the first registration of a three-dimensional shape as a trademark recognized by the IPHC.

This article first briefly explains the framework of the registration system for three-dimensional trademarks of goods or packaging of goods, provides some data on registrations of three-dimensional trademarks, and examines the IPHC decisions.

1. Requirements of registration of three-dimensional trademarks

On April 1, 1997 Japan adopted a registration system, with strict requirements, for three-dimensional trademarks. The requirements of registration are as follows. (Articles cited are provisions of Japan’s Trademark Law.)

(1) If a trademark consists solely of a mark indicating, in a common manner, the shape of goods or packaging, it may not be registered. (Article 3, Section 1, Paragraph 3)

(2) Notwithstanding Article 3, Section 1, Paragraph 3, a trademark may be registered if, as the result of the use of the trademark, consumers are able to recognize the goods bearing the trademark as those pertaining to a business of a particular person. (Article 3, Section 2: secondary meaning)

(3) If a trademark consists solely of a three-dimensional shape of goods or the packaging of goods that is indispensable for the goods or their packaging to properly function, it cannot be registered. (Article 4, Section 1, Paragraph18)

The first requirement is considered very difficult to meet, because it appears to mean that any shape of goods or packaging of goods as such cannot be registered as a three-dimensional trademark, insofar as registration is sought for merely the shape of goods or packaging. The requirement includes the doctrine of “aesthetic functionality” that applies to the appearance of goods. Thus, under requirement (1) only a three-dimensional trademark or packaging of goods with respect to which no one can identify what its shape represents can be registered. The Examination “Guidelines” prepared by JPO explain as follows the phrase “in a common manner” that appears in Article 3, Section1, Paragraph 3 of the Trademark Law.

Even though a shape is uniquely changed or decorated, when consumers perceive those changes or decorations to be within the scope of the shape that is adopted by the industry involved in the transaction of the relevant goods, it will be found that the three-dimensional shape does not go beyond the scope of the shape of designated goods. Such a trademark will be deemed to lack distinctiveness.

The JPO examiners apply these Articles in order when they examine applications for three-dimensional trademarks. Thus, even if a threedimensional shape trademark can satisfy requirements (1) and (2), if the shape is indispensable for such goods or their packaging to properly function, the trademark cannot be registered. The third requirement may be called the “functionality doctrine” that applies to utilitarian aspects of goods. If the product feature is essential to the use or purpose of the product, that is, alternative designs are not available or the cost or quality of the goods has advantages in terms of method of manufacture, the relevant three-dimensional shape trademark should be held to be functional, and thus ineligible for protection. However, there are no cases denying three-dimensional shape trademarks on the basis of Article 4, Section 1 Paragraph 18.

Despite such stringent requirements, about 1,400 three-dimensional shape trademarks have been registered over the past 10 years. Most, however, are not related to the shapes of the goods or packaging of the goods themselves that are specified under the registered trademarks. They are, for example, statues such as Colonel Sanders of Kentucky Fried Chicken for fried chicken, a variety of figures or shapes of goods that are not related to the shapes of the goods or packaging of the goods themselves that are specified under the registrations, or those having word marks or design marks already registered.

In general, packaging of goods bears word marks or two-dimensional design marks already registered as trademarks for the goods contained in the packaging. Many of such kinds of packaging have been registered as three-dimensional shape trademarks. However, the Guidelines explain that if words, letters, devices or figures are not recognized as indicating the source or origin of the goods, but merely as decoration or decorative design used to increase the aesthetic value of the packaging, the relevant three-dimensional shape trademark cannot be registered. Thus, it will not be said that threedimensional trademarks with registered word marks are true threedimensional trademarks.

On the other hand, many applications for trademark registration of three-dimensional packaging shapes of goods having no word marks or two- dimensional device marks have been denied, on the ground that they lack distinctiveness, or have failed to acquire secondary meaning.

2.Examples of registration of three-dimensional trademarks

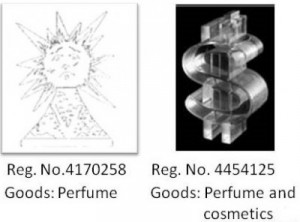

Some three-dimensional trademarks of goods or packaging have been registered as being themselves inherently distinctive. For example:

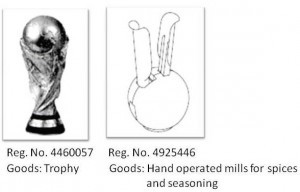

These are bottles of perfume. Consumers very likely cannot perceive them as merely perfume bottles, and the changes or decorations go beyond the scope of the shape that is usually adopted by the industry involved in transactions of perfume goods. The three-dimensional trademarks as shown below have also been held inherently distinctive and have been registered.

The picture on the left above shows the famous world championship soccer trophy. The applicant once incurred a preliminary denial, but then succeeded by filing an argument. The shape was held to be unique and original in external appearance. The shape of the mill, on the right, has been registered at the level of the TTAB. It is held that the shape is quite different from the usual shape of mills and cannot be perceived as a hand operated mill for spices and seasoning. The decision on the hand mill is the first in which the TTAB has granted a registration for a three-dimensional shape trademark on the ground of inherent distinctiveness.

Some three-dimensional shape trademarks have been registered as having acquired secondary meaning, for example, those shown below.

Note that there are no word marks on the six registered threedimensional trademarks shown above. Some goods on the markets have word marks on them that can function as a trademark, and some do not. The JPO has been accepting trademark registration of a three-dimensional shape of goods if the distinctive word trademarks are affixed to the shape.

On the other hand, many three-dimensional trademarks of goods without word trademarks or distinctive device marks have been denied registration, on the ground that the shape as such of goods does not basically indicate the source or origin of the goods but rather provides consumers with aesthetic appeal. And as the goods on the market bear distinctive word trademarks, consumers purchase or distinguish goods from others by relying on the word trademarks, which are usually superior to the goods’ appearance as an indicator of the goods’ source or origin. In other words, the JPO opinion seems to imply that the three-dimensional appearance of goods does not basically serve as a trademark.

It will be true that a three-dimensional product or packaging shape will not be found inherently distinctive unless it is unusual and conceptually separated in addition to being likely to serve as an indication of the source or origin of the goods.

3.The shape of packaging

The PO’s opinion is more stringent regarding the shape of packaging. As a practical matter, all existing packaging on the market has word or device marks that can serve as trademarks. The opinion of the JPO and the courts is that such word or device marks have more appeal to consumers when they purchase goods than the shape of the packaging itself. If this view is correct, there will be no chance for the shape of packaging to be registered as a trademark. Of course, there are many criticisms of this view.

A three-dimensional bottle trademark, without any word marks, for whisky sold by Suntory Ltd. for about 70 years, was denied registration by the TTAB, and the Tokyo High Court turned down the appeal, notwithstanding market research indicating that about 74 % of consumers perceived the bottle design as indicating the source or origin of the whisky. The Court ruled that the bottle, when actually sold, bears the word mark SUNTORY, and that when purchasing the whisky consumers rely upon the word mark rather than the shape of the bottle.

The application for registration of a three-dimensional trademark for a Coca-Cola bottle without the word “Coca-Cola” on the surface of the bottle was recently denied by the TTAB. The case has been appealed to the IPHC. We are hoping for a judgment reversing the PO’s decision.

4.Judgment on a chick-shaped trademark

A three-dimensional chick-shaped trademark of cakes was registered in the name of Hiyoko Co., Ltd. (“HIYOKO”) located in Fukuoka on the basis that it had acquired secondary meaning. HIYOKO admitted that the mark consists solely of a shape indicating in a common manner the shape of a chick, and that it falls within Article 3,Section 1, Paragraph 3 of the Trademark Law, which does not permit registration of such trademarks. In other words, HIYOKO had no objections to the conclusion that the shape is inherently descriptive. In the course of examination at the TTAB, HIYOKO submitted a great deal of evidence; based on the evidence the TTAB held that the shape had acquired secondary meaning.

Based on the three-dimensional trademark registration, HIYOKO then commenced court action against Nikakudo Co., Ltd. (“NIKAKUDO”), also located in Fukuoka, demanding that NIKAKUDO discontinue use of a similar configuration of a bird-shaped cake. NIKAKUDO filed a request for an invalidation trial against the registration with the TTAB, which rejected the request. The case was appealed to the IPHC. Shown below are the shapes of the relevant sweets sold by both HIYOKO (left) and NIKAKUDO (right).

The issue considered by the IPHC was whether HIYOKO’s chickshaped cakes had acquired secondary meaning under Article 3, Section 2 of the Trademark Law. The IPHC first pointed out the criteria for applying the provision in connection with a three-dimensional trademark. They are (1) that the trademark must be used exclusively, continuously and for a long time, (2) that two-dimensional words or devices incidentally used with the three-dimensional shape should be disregarded, and 3) that the acquisition of secondary meaning must be decided if the trademark has been recognized throughout Japan as indicating the source or origin of the goods. Based on these criteria, the IPHC held that HIYOKO’s cakes had not acquired secondary meaning.

The IPHC ruled that the word mark “Hiyoko” (hiyoko means “chick”) had been well known to consumers mainly in the Kyushu and Kanto areas (most of HIYOKO’s shops are in these areas), but that HIYOKO’s three-dimensional trademark had not yet acquired secondary meaning throughout Japan. The IPHC reasoned as follows.

(1) It has been proved that HIYOKO’s chick-shaped cakes have been sold since 1913, that the turnover at the time of registration (2003) was US$400 million, that the advertising expenditures from 1987 to 2003 were about US$6.5 million per year, and that there had been extensive advertising through newspapers, magazines and TV commercials. However, the chick-shaped cakes are each wrapped in paper bearing the word mark “Hiyoko” and packed in a box bearing the word mark “Hiyoko.” In the advertising the word mark “Hiyoko” is always used along with the chick-shaped cakes.

(2) There are 23 different companies in several areas of Japan, which have been selling bird-shaped cakes, which are held as similar to HIYOKO’s chick-shaped cakes. These include NIKAKUDO’s chick-shaped cakes, sold in large quantity since 1965. These different companies’ bird-shaped cakes were being sold well before the registration date (August 29, 2003) of HIYOKO’s three-dimensional trademark and were known to consumers as their own goods.

(3) In addition to the above bird-shaped cakes, historically a similar type of cakes existed in the Edo Era (before 1867), which means that they are extremely common and traditional in Japan.

(4) The shape of HIYOKO’s chick-shaped cakes is not so arbitrary; rather it should be held that it is rather simple.

(5) HIYOKO’s shops are located in limited areas of Japan (in Kyushu and the Kanto area, including Fukuoka and Tokyo).

Thus, even considering the high product sales and frequent advertising of the goods, it should be held that HIYOKO’s three-dimensional chick-shaped trademark had not acquired secondary meaning to justify legal protection and should be ruled invalid.

5.Judgment on a pen-shaped flashlight trademark

Mag Instrument, Inc. (MAG) filed on January 19, 2001 an application for registration of a trademark composed of a three-dimensional penshaped flashlight without any word mark thereon, as shown below.

The examiner rejected the application on November 15, 2002, and an appeal to the TTAB was filed on February 7, 2003. The TTAB issued a decision rejecting the appeal on August 21, 2006. The decision is based on Article 3, Section 1, Paragraph 3 of the Trademark Law, and denies the assertion of the acquisition of secondary meaning. The rationale of the rejection based on Article 3, Section 1 Paragraph 3 follows the “Guidelines” and similar rejections have been issued in many cases. Regarding the issue of whether the flashlight has obtained secondary meaning, the TTAB held that although a large number of the flashlights had been sold, and they were introduced in a number of magazines and newspapers, the flashlights all bore the words “MAG INSTRUMENT” and a mark “MINI MAGLITE” with circle “R”, and that there was no evidence proving the sales of the flashlight without such word and mark, and that therefore it should not be recognized that the trademark composed of a threedimensional pen-shaped flashlight without any word mark had obtained secondary meaning.

MAG appealed to IPHC on December 27, 2006 and argued that the mark is inherently distinctive, and that even if it is not distinctive, it has obtained secondary meaning. MAG’s argument regarding inherent distinctiveness is as follows.

1) That the shape has unprecedentedly unique features that other flashlights do not have;

2) That there are no flashlights the same as or similar to MAG’s flashlight manufactured by other makers;

3) That it has received design awards in USA, Germany, France, Japan, etc., and is protected by copyright in Sweden, Hong Kong and UK;

4) That many counterfeits without any marks appeared on the Japanese markets, but disappeared from the markets due to court actions taken by MAG and the results of negotiations with counterfeiters admitting that they had copied MAG’s well-known flashlight;

5) In more than 30 foreign countries as well as in Japan, court actions have successfully been taken against counterfeiters;

6) MAG has filed a similar application in 25 countries and obtained a registration for the three-dimensional pen-shaped flashlight in 22 countries, including USA, Germany, Norway, Switzerland.

The IPHC has not accepted these arguments as well grounded. It is held that, insofar as the total appearance of product’s design is within the scope of selection from the point of view of “product’s function and the esthetic appearance of products”, it falls under Article 3, Section 1 Paragraph 3, even if the appearance of the penshaped flashlight has an unprecedented unique appearance that is not seen in other flashlights. (The IPHC does not mention about the designs having “unprecedented unique appearance” that is adopted from any other point of view. As mentioned above, the TTAB held that the hand-operated mill registered as a three-dimensional shape trademark is quite different from the usual shape of mills and cannot be perceived as a hand operated mill for spices and seasoning. Thus, we can say that even if a product has an unusual shape, insofar as it can be perceived as the shape of the product, it will be impossible to obtain a registration as a three-dimensional trademark under Article 3, Section 1 Paragraph 3 of the Trademark Law.)

However, the IPHC has reversed the TTAB decision refusing a registration based on Article 3, Section 2, accepting MAG’s following assertion and evidence that the trademark has obtained secondary meaning.

1) That the pen-shaped flashlight (MINI MAGLITE) has been on the Japanese market since 1986 without any change in the design: the sales turnovers between April 1999 and March 2000 and between April 2000 and March 2001 were more than US$ 4.7 million by selling 607,000 units, and US$ 4 million by selling 550,000 units, respectively in Japan; the flashlight is now sold in about 2,700 shops as well as via Internet online shops; the advertisement expenditures amounted US$ 1.9 million from 1997 to 2001;

2) That it has been granted awards and housed in museums in USA and Germany, and received a prestigious design prize –a prize for its design in Japan in 1990;

3) That many counterfeiters have been stopped by court actions taken by MAG, and there are no flashlights the same as or similar to MAG’s flashlight manufactured by other makers at the present time;

4) That due to the remarkable and unique design, the advertisements are focused on the appearance of the design so as to give appeal to the appearance of the design.

The IPHC briefly commented on the point of the existence of the word “MAG INSTRUMENT” and a mark “MINI MAGLITE” with circle “R”, stating that they are written in smaller sizes than the whole appearance of flashlight and will not be barriers for judging that the shape of the flashlight has obtained secondary meaning as the identifier of the origin of the flashlight.

6.Conclusion

As mentioned above, the Japanese Patent Office and the courts have pointed out the existence of distinctive two-dimensional word or device marks on goods or packaging in the market in order to deny registration of three-dimensional trademarks, ruling that such distinctive word or device marks are indicators of the source or origin of the goods. It is naturally understood that distinctive word or device marks are in general superior to product configuration as identifiers of the source or origin of goods. It may be true that it is less common for consumers to recognize the design of goods, as opposed to packaging features, as an indication of source. The design of goods is more likely to be considered merely as an aesthetic, utilitarian or ornamental aspect of the goods in comparison with packaging features. Thus, a different approach should be taken regarding packaging configuration. Packaging without any two-dimensional word or

device trademarks does not and will not exist in the market. Since in our view, the appearance of packaging could serve as the signifier of the source or origin of goods in addition to or separately from the word or device marks represented on the goods, I must conclude that the approach taken by the Japanese Patent Office and courts to decide whether a three-dimensional packaging trademark has acquired secondary meaning overlooks the purpose and intention of introducing the protection of three-dimensional trademarks.

商標分野の他の法律情報

お電話でのお問合せ

03-3270-6641(代表)